- Home

- Clayborne Carson

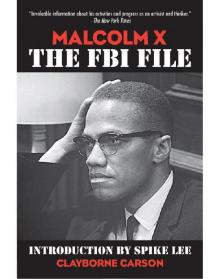

Malcolm X

Malcolm X Read online

Edited FBI file copyright © 1991, 2012 by David Gallen

Commentary copyright © 1991, 2012 by Clayborne Carson

Introduction copyright © 1991, 2012 by Spike Lee

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61608-376-2

Printed in the United States of America

For my son, David Malcolm Carson

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The publisher gratefully acknowledges permissions to reprint from the following:

Amsterdam News, for excerpts throughout.

Barry Gray and WOR Radio, for interview June 8, 1964.

William Kunstler, for WMCA Radio interview June 8, 1964.

Irv Kupcinet, for WBKB Television interview January 30, 1965.

Los Angeles Herald Dispatch, for excerpts throughout.

New York Post, for “Malcolm X to Elijah: Let’s End the Fighting,” June 26, 1964. © 1964 by New York Post Company, Inc.

The New York Times, for “Malcolm X Seeks U.N. Negro Debate,” August 13, 1964. © 1964 by The New York Times Company, Inc.

Omaha World-Herald, for “Malcolm X’s Talk June 30,” June 15, 1964; “Malcolm X’s Talk Tonight,” June 30, 1964; “Malcolm X Declares Anything Whites Can Do Blacks Can Do Better,” by Duane Snodgrass, July 1, 1964.

Pittsburgh Courier, for excerpts throughout.

Mike Wallace, for WNTA Television interviews in “The Hate That Hate Produced,” July 13-17, 1959.

Washington Post Company, Inc., for excerpts from New York Herald Tribune, April 26, 1964, and June 16, 1964. © 1964 by New York Herald Tribune, Inc. All rights reserved.

Westinghouse Broadcasting Company and WBZ Radio (Boston), for interview on “The Bob Kennedy Show,” March 24, 1964.

WMAL Radio, for interview February 2, 1963.

WUST Radio, for interview May 12, 1963.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Part I: Malcolm and the American State

Social Origins of Malcolm’s Nationalism

Malcolm and the FBI

Politicization of Nationalism

Malcolm’s Ambiguous Political Legacy

Part II: Chronology

Part III: The FBI File

Section 1

Section 2

Section 3

Section 4

Section 5

Section 6

Section 7

Section 8

Section 9

Section 10

Section 11

Section 12

Section 13

Section 14

Section 15

Section 16

Section 17

Section 18

Section 19

Elsur Logs

Appendix

Index

INTRODUCTION

When I was growing up one of my favorite shows on television was THE FBI (Righter of the Wronged, Protector of the Weak). I liked how Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., the FBI Big Cheese, every week outguessed, outsmarted and outmaneuvered crooks, Communists, thieves, murderers, to uphold truth, justice and the American way. I know I couldn’t have been the only one who watched it; the man himself, J. Edgar Hoover, loved it also. Back in those days I was young and believed the FBI, CIA and the police were the good guys; they were righteous. Over time, I found out, like many others, this isn’t the case at all, except in television and the movies.

One can safely say the Federal Bureau of Investigation has never been a friend to African-Americans. As far back as Marcus Garvey and A. Phillip Randolph the Bureau has more than kept its watchful eye on black leaders trying to uplift their people.

I was fascinated reading this book. At the same time, though, I found it frightening. We all live in a wicked country where the government can and will do anything to keep people in check.

I might add that I see the FBI, CIA and the police departments around this country as one and the same. They are all in cahoots and along with the Nation of Islam they all played a part in the assassination of Malcolm X. Who else? King? Both Kennedys? Evers? Hampton? The list goes on and on.

J. Edgar Hoover was a known racist and he did all he could and more to stop any movement by or on behalf of blacks, all under the guise of protecting democrary.

This book chronicles the growth in the evolution of Malcolm from his early “white man is the devil” days to his later, more developed world outlook right before he was killed. One can see that the Bureau and agencies like it cannot work successfully without informants. They had plants around Malcolm at the highest levels of all his organizations: The Nation of Islam, Muslim Mosque, Inc., and the Organization of Afro-American Unity. To me, that’s the sad part. Malcolm was sold out. A house nigger turned him into Massa just like one did Nat Turner and countless others. It’s also ironic that Brother Gene, one of Malcolm’s bodyguards who gave him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation seconds after he’d been shot down and was dying, also proved to be a police informant. The Bureau knew Malcolm’s every move, knew he was being hunted down, but stood back and let him and Elijah fight it out in public (a dispute which they encouraged no doubt).

I’m still surprised they even let these papers out. Turn that around and wonder what was destroyed: What documents will we never know about?

It’s 1991 and the Federal Bureau of Investigation we know from television and Mississippi Burning are far, far from reality. Fortunately, there are books like this that combat these Walt Disney/John Wayne bogus images. The Bureau, however, would make THE GREAT AMERICAN GANGSTER MOVIE.

—Spike Lee

Part I

Malcolm and the American State

Malcolm and the American State

For maximum effectiveness of the Counterintelligence Program, and to prevent wasted effort, long-range goals are being set.

1. Prevent the coalition of militant black nationalist groups. In unity there is strength; a truism that is no less valid for all its triteness. An effective coalition of black nationalist groups might be the first step toward a real “Mau” in America, the beginning of a true black revolution.

2. Prevent the rise of a “messiah” who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement. Malcolm X might have been such a “messiah”; he is the martyr of the movement today. Martin Luther King, Stokely Carmichael and Elijah Muhammad all aspire to this position. Elijah Muhammad is less of a threat because of his age. King could be a very real contender for this position should he abandon his supposed “obedience” to “white, liberal doctrines” (nonviolence) and embrace black nationalism. . . .

—FBI memorandum, March 4, 1968.

Malcolm X’s political and historical significance increased after his assassination. His public statements as a minister and political leader reached mainly a black urban audience while millions of every race read his posthumously published autobiography and speeches

. He gained prominence as a caustic critic of civil rights leaders, but by the end of his life his evolving ideas had converged with the militant racial consciousness stimulated by the civil rights protest movement. During his public career, he was affiliated with one of the smaller African-American religious groups and never participated in the major national meetings of black leaders; yet he is remembered as one of the most influential political leaders of modern times. To some admirers he became an icon—a heroic, almost mythological, figure whose arousing orations have become indisputable political wisdom. To detractors he remains a dangerous symbol of black separatism and anti-white demagoguery. One of the most widely discussed and controversial African-American leaders of this century, Malcolm remains insufficiently understood, the subject of remarkably little serious biographical and historical research.

This edition of Malcolm X’s FBI surveillance file seeks to retify a particularly serious deficiency in previous writings on Malcolm—that is, the failure to study him within the context of American racial politics during the 1950s and 1960s. The surveillance reports document Malcolm’s life from his final years in prison during the early 1950s through the time of his assassination in February 1965. They trace Malcolm’s movement from the narrowly religious perspective of the Nation of Islam toward a broader Pan-Africanist worldview. The file illuminates his religious and political world suggesting the extent to which his ideas and activities were perceived as threatening to the American state. When examined in the context of the FBI’s overall surveillance of black militancy, Malcolm’s FBI file clarifies his role in modern African-American politics.

Although some writings about Malcolm X have referred to the FBI file, most biographical accounts have not placed him within the framework of national or international politics. Instead, Malcolm has usually been portrayed as an exceptional individual whose unique experiences inspired his distinctive ideas, as a person affecting African-American politics rather than being affected by the constantly changing political environment.1 Even Malcolm’s relationships and activities within the Nation of Islam remained shrouded in rumor and mystery, despite the crucial role that organization played in Malcolm’s ideological development.

Moreover, research regarding Malcolm remains largely uninformed by the outpouring of scholarly studies of his main ideological competitor, Martin Luther King, Jr. Although King, like Malcolm, was a remarkable orator, recent writings on him have placed King within the wider framework of African-American political and religious history.2 Similarly broadly focused studies are needed in order to understand Malcolm’s evolving role in a multifaceted African-American freedom struggle that shaped his ideas even as he influenced its direction. Malcolm and King were articulate advocates of distinctive philosophies and political strategies, but neither leader’s historical significance can be equated solely with the emotive power of his words. Both Malcolm and King sought to provide guidance for a mass struggle that generated its own ideas and leaders. Rather than simply followers of Malcolm or King, the activists, organizers, and community leaders who constituted the grass roots of the freedom struggle magnified both leaders’ political impact.

Instead of extensive research based on sources produced at the time, popular and scholarly understanding of Malcolm X derives largely from published texts of his speeches and from The Autobiography of Malcolm X, a vivid and enlightening, yet undocumented, narrative prepared by Alex Haley. Haley shaped his subject’s recollections into a moving account of Malcolm’s transformation from abused child to ward to criminal to religious proselytizer to radical Pan-Africanist. The autobiography is an American literary classic that has enriched the lives of many readers. It elicits empathy, revealing the world through its narrator’s eyes, but it is less successful as social and political history. Malcolm’s political ideas become conclusions drawn solely from his personal experiences. His changing attitudes toward whites becomes the central focus of the narrative, while his political influences, contacts, and activities are reduced to subthemes. All serious study of Malcolm X must begin with the Autobiography; unfortunately, many works on him do not extend beyond the biographical and historical information provided by Malcolm himself.3

1. Social Origins of Malcolm’s Nationalism

Like most autobiographies, Malcolm’s account of his life was intended to explain how he came to enlightenment and fulfillment, but his narrative is incomplete and misleading. Malcolm’s early experiences limited his subsequent political choices but do not explain them. Malcolm’s conversion to Elijah Muhammad’s doctrines was a rejection rather than a culmination of his previous life. He repudiated the Christian teachings of his childhood and affiliated with a religious organization he had never previously encountered. He insisted that the major national civil rights groups and their middle-class leaders did not represent needs of the black masses, but, before joining the Nation of Islam, he had never been affiliated with any African-American advancement organization. Despite his fervent advocacy of racial unity and institutional development, he was, ironically, an outsider with respect to the most important African-American institutions. His life was spent mainly as an angry, though insightful, critic, hurling challenges from the margins of black institutional life. With some justification, he saw himself as a leader uniquely capable of arousing discontented African Americans that leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr., could not reach. During most of his life, however, his status as an outsider prevented him from having the type of impact on the direction of African-American politics that he would achieve as a marbyr.

Malcolm’s black nationalism derived, ironically, from his exclusion from the African-American social and cultural mainstream. Although his parents, Louise and Earl Little, were organizers for Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), his childhood experiences did not connect him to the enduring institutions of black life. Rather than memories of a nurturing African-American household, Malcolm’s autobiography emphasized the white forces that destroyed his family. He remembered racist whites forcing his family to move from Omaha, Nebraska, where he was born in 1925, to Milwaukee, then to Lansing, Michigan, and finally to a home outside East Lansing. Malcolm gives few indications that he was involved as a child in African-American social life. Malcolm remembered his father as an embittered itinerant preacher who, despite his Garveyite sympathies, displayed and infused Malcolm with ambivalent racial attitudes. “I actually believe that as anti-white as my father was,” Malcolm surmised, “he was subconsciously so afflicted with the white man’s brainwashing of Negroes that he inclined to favor the light ones, and I was his lightest child.” Watching his father deliver sermons, Malcolm was “confused and amazed” by his emotional preaching and acquired “very little respect for most people who represented religion.” Taken to UNIA meetings by his father, Malcolm was unmoved by the message of racial pride. “My image of Africa, at that time, was of naked savages, cannibals, monkeys and tigers and steaming jungles.” Malcolm felt that his mother treated him more harshly than his siblings because his light complexion stirred memories of her own mixed-race ancestry. Neither of Malcolm’s parents were able to shelter him or provide him with dependable resources to deal with the racism of the surrounding world. When Earl Little was killed in 1931, six-year-old Malcolm believed rumors that “the white Black Legion had finally gotten him.”4 Afterwards, Malcolm’s family life rapidly deteriorated. His mother resented her dependence on welfare assistance. As she progressively lost her sanity, Malcolm became more and more incorrigible. At the age of thirteen, Malcolm was removed from his family entirely and sent to reform school.

In contrast to Malcolm’s experience of a disintegrating family life and social marginalization, Martin Luther King, Jr., his principle ideological adversary, spent his childhood within a stable, nurturing African-American family and community.5 “My parents have always lived together very intimately, and I can hardly remember a time that they ever argued,” King once recalled. Growing up in the house his grandf

ather, A. D. Williams, had purchased two decades before King’s birth in 1929, the family’s roots in the Atlanta black community extended to the 1890s, when Williams had become pastor of Ebenezer Baptist church. After Williams’s death in 1931, Martin Luther King, Sr. became Ebenezer’s Pastor. The church became King, Jr.’s “second home”; Sunday School was where he met his best friends and developed “the capacity for getting along with people.” Although he, like Malcolm, came to dislike the emotionalism of black religious practice, he developed a lifelong attachment to the black Baptist church and an enduring admiration for his father’s “noble example.”6 King and his family developed strong ties to Atlanta’s black institutions, including businesses, civil rights organizations, and colleges such as Morehouse and Spelman. While Malcolm’s family experienced economic hardship during the Depression years, King “never experienced the feeling of not having the basic necessities of life.” Both Malcolm and King acquired antielitist attitudes during their childhoods, but the former resented middle-class blacks while the latter acquired a sense of noblesse oblige. As a teenager, Malcolm ended his schooling after the eighth grade when he was discouraged from aspiring to be a professional. King completed doctoral studies and saw education as a route to personal success and a career of service to the black community.

Both Malcolm and King recalled having anti-white attitudes during their formative years, but white people occupied a much more central place for Malcolm as a young man than for King, who had little contact with whites as a youth. Malcolm’s evolving attitudes toward whites were complex and volatile, serving as the underlying theme of his autobiography. As a child, his mother took him to meetings of white Seventh Day Adventists, whom Malcolm recalled as “the friendliest white people I had ever seen.”7 His account of his youth includes both descriptions of encounters with white racism and indications of his own ambivalent feelings toward whites. Often the only black in his class, he refrained from participating in school social life. He admitted nevertheless that he secretly “went for some of the white girls, and some of them went for me, too.” Elected president of his eighth grade school class, he concedes that he was proud: “In fact, by then, I didn’t really have much feeling about being a Negro, because I was trying so hard, in every way I could, to be white.”8 After moving to Boston in 1941, Malcolm soon straightened his hair in order to look more “white,” and brushed off a black, middle-class woman named Laura in order to pursue his white lover. King, for his part, reacted to a childhood rejection by a white friend by determining to “hate every white person” and thereafter had little social contact with whites until his college years.9 Spending his formative years as part of an African-American elite, he resented white racial prejudice but was rarely personally affected by it. His racial identity most often brought him rewards rather than punishments.

Malcolm X

Malcolm X